In the American Southwest, where deer and coyotes roam free and the prickly pear cactus grows wild, there’s a new outsider ready to cause trouble. But there’s no need for sheriffs and masked vigilantes to be on the lookout for rogue cowboys galloping on horseback. And there’s a new hero on the scene: scientists. They must rise to the occasion. And quickly. Or else.

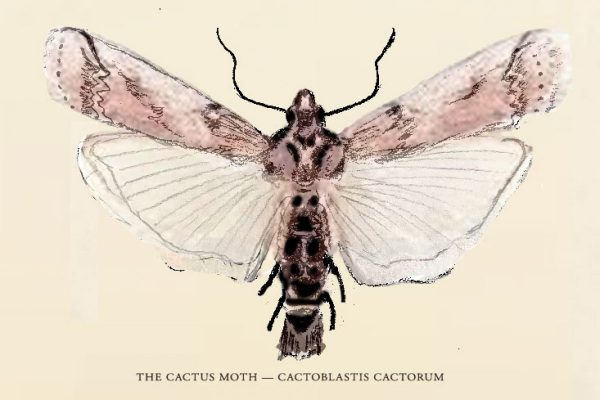

Or else South America’s Cactoblastis cactorum, an invasive cactus moth with a wingspan about the same size as the length of a standard paper clip, will devastate the Southwest’s prickly pear. The cactus, known for its flat pads and pear-shaped edible fruit, is the state cactus of Texas and a vital member of the ecosystem. It’s a source of food and shelter for mammals, birds, reptiles and insects; it acts as a nurse plant, providing a safe space for smaller plants to germinate and grow. The agricultural economy relies on prickly pear to feed cattle. Even Mexican cuisine depends on prickly pear to make nopales.

This cactus moth eats the prickly pear’s insides, causing the plants to collapse, and it has wiped out populations of the plant before. In the 1920s, Australians used the moth as a biological control when prickly pear took over the bushland. At the peak of the prickly pear infestation, there was as much as 60 million acres infected. In just a few years after the moth was introduced, the prickly pear became almost nonexistent. This success led to the moth being used across Caribbean islands for the same reason.

But in the late 1980s, the moth made its U.S. debut in the Florida Keys, causing widespread damage to the native North American plant and raising fears that the insects could move on to Texas and Mexico. Those areas have a high density of prickly pear and temperate weather, ideal conditions for the moth to spread. It’s the perfect recipe for disaster.

Since 2007, the scientists at Brackenridge Field Laboratory, including director Lawrence Gilbert and research scientist Rob Plowes, in partnership with scientists and labs in Florida, Mexico and Argentina, have been racing against the clock to prevent a repeat of what happened in Florida and Down Under.

“Our concerns were heightened,” Plowes says. “We actually took the initiative to do some preemptive work because we realized that …”

“… they were going to get here,” says Gilbert, a professor in the Department of Integrative Biology.

And they did. In 2017, there was an unconfirmed sighting of the cactus moth along the Texas coast. By December 2018, there were four recorded reports of the moth in the state. More have been sighted over the past year and as recently as early February. With little data, it’s hard to predict how quickly the cactus moth will spread. It might be helped inland by the Gulf breeze, but colder conditions could prevent a second generation of moths. Westward spread might be slower, but warmer weather gives the moth better chances of survival.

Plowes estimates that the moth could reach Mexico within three to five years, but the lab is continuously working to find the rate of spread so it may better alert people about potential damage.

Twice a week, laboratory research assistant Caroline Black drives more than nine hours a day, setting up traps to track where the moth is headed and how quickly it’s spreading. Black begins her field work from her home in Austin and drives between towns near Columbus and Victoria. Along the way, she sets wing traps and tube traps, each containing a version of sticky paper combined with a bait, and records what they catch.

The drives are filled with the coast’s lush scenery. Prickly pear plants merely dot the grassy landscape. It’s nothing like the iconic desert backdrops seen in Western movies, so the cactus doesn’t always appear to be in imminent danger.

“It’s easy to forget how high stakes it is when you’re driving around East Texas since it’s not super cactus land everywhere that I’ve driven,” Black says. “But then I go on hikes on my personal days, and I see all of these cactus everywhere. If this moth gets any further in, I’ve seen how quickly it destroys one huge cactus. I can only imagine how quickly it’ll just blow through this population.”

A few months after Black joined the field lab, doctoral student Colin Morrison, Plowes, research associate Nathan Jones and Gilbert published an article in Ecological Entomology. The article detailed the group’s research on four types of prickly pear to see if there were any qualities that could deter the moth. They hoped there would be some chemical response by the cactus to fight off the intruder, but there were few variances to be found. All four tested species face consumption and eradication by the invasive moth.

Morrison, who became a graduate research assistant on the project in 2019, designed the experiment, collected and analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript for the article. He says he wasn’t surprised by the results. It was one of the primary hypotheses going into the project.

“This kind of a project is a little bit more than just basic understanding for the sake of it,” Morrison says. “There’s urgency, and there’s a lot of conservation and land management factors tied to it. We were hoping that there would be some big differences, but unfortunately, there weren’t.”

The scientists are also exploring the option of bringing in a parasitic wasp (Apanteles opuntiarum) as a biological control, a parallel to how the cactus moth was used as a control in Australia. Although this wasp is native to South America and a known parasitoid for the invasive cactus moth, enough testing must be conducted to determine whether the wasp will be host-specific. It needs to attack the invasive moths, not other native cactus moths. Additionally, it’s important that the wasp is sustainable, to prevent having to reintroduce the wasps each year, as well as effective.

The research on the wasps picks up where Floridian researchers left off, and that experience has helped control the budget for the entire operation. Plowes estimates it will cost $500,000 to $1 million per year for three years to release the wasps with proper scientific measures. Once released, the wasps will spawn more research on the spread of nonnative species.

“Like in the medical field, when you’re doing a vaccine, or any kind of a prophylactic that you’re applying to the population, you do follow-up studies to make sure that what you thought was going to happen is happening,” Gilbert says. “You can’t just dump something out here and hope it works. You have to keep working on it.”

Plowes says it may take 18 months to two years before the wasp is released. He imagines it will take up to a year to get the correct documentation and approvals in order with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The next stage entails getting permits to import the wasps from South America. Given the concerns for prickly pear across the border, Mexico will be included in the approval process.

“This is a multicountry enterprise and effort, and it takes a lot of different labs working on different parts of it,” Plowes says. “We’re playing our role, but we really have to respect and acknowledge the huge effort that’s already gone ahead. The folks in Florida have had these moths for nearly 30 years, and their experience is devastating.”

“We’ve had a little bit of time in hand, but now we’re scrambling to close that final mile.”