Someday, when you think back to life during 2020, what will you remember? Protests and a protracted presidential election? Masks and overflowing ICUs? Bleach and bread-baking tutorials?

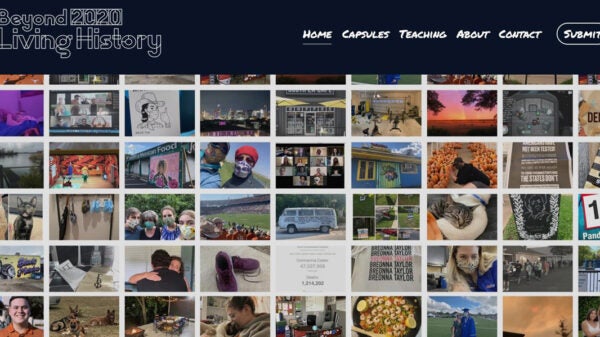

History is made every day, but 2020 seemed especially full of momentous moments. “Beyond 2020 Living History” seeks to collect these memories as they’re being made. In fall 2020, Daina Ramey Berry, the Oliver H. Radkey Regents Professor and chair of the Department of History, began collecting photos and stories — digital time capsules — from staff and faculty members, students and alumni at 2020livinghistory.com, with help from other members of the History Department, including professor Adam Clulow, who built the website. Berry and Clulow talked with Texas Connect about the project; answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

What prompted you to start collecting these time capsules?

Berry: As historians, we often analyze moments that occurred in the past, but we knew that this would be a year that scholars would study in the future, and we wanted to help curate that learning by capturing it in a real, personal way.

What do you think sets 2020 apart from other time periods?

Clulow: We’ve had pandemics; we’ve had political protests and elections; we’ve had environmental catastrophes, but rarely have so many different forces come together in a single year. In 2020, the legacies of racism and institutional violence, ongoing inequities in medicine and access to care, and patterns of environmental exploitation collided against each other like huge tectonic plates. I’ve lived through a lot of change in my life, but rarely have I felt the forces of history coming together so clearly as they did in 2020.

This was an extraordinary year because so much was happening but also because we were experiencing it together and apart at the same time. The Beyond 2020 project was born in part because we were talking to so many students who felt incredibly isolated as they couldn’t come to campus or participate in any of the usual rituals of university life.

How many submissions have you received so far?

Clulow: To be honest, we stopped keeping track as submissions keep trickling in from individuals or from class assignments, and we’re always updating the website. Once we reached a critical mass (around 40 capsules) including submissions from undergraduates, graduate students, staff and faculty, we felt we had something that was broadly representative. We continue to update the site when new submissions come in.

What are some of the themes you’ve seen come up in the submissions?

Berry: Isolation, fear, family, love, solidarity, hope, camaraderie, Mother Nature, human rights, discord, distrust, anger, health, community, home. I always like people to review the capsules and tell us what themes they recognize.

Clulow: We had feared that every capsule might look the same, beginning with the ubiquitous mask and ending with the omnipresent Zoom loading screen. Instead, they were both more intimate and more varied than we had imagined. The capsules were intensely personal, opening an unexpected window into the lives of students, staff and faculty.

If there is one theme that resonates through the capsules, it is loss. The capsules are filled with loss — not so much the loss of a loved one, although that fear was omnipresent, but the loss of shared space. Universities thrive on their campuses, which provide spaces for myriad encounters with people and ideas. 2020 closed these off, reducing shared space for many students down to virtually zero. This loss ran like a thread through many of the capsules.

Submissions were limited to UT staff, faculty and students. How important was it to you not only to memorialize history but also, in doing so, to support the UT community?

Berry: We see this project as a way to embrace history and support our UT community by providing an outlet for individual and communal expression. This work will be meaningful for those who study this time period in the future, but it is also a useful coping mechanism for those who want to express their feelings about the events of 2020 and beyond.

Clulow: We had initially talked about making the project accessible to anyone, but the best decision we ever made was to limit this to the UT community. Our motivation came from conversations with students, both undergraduate and graduate, who felt trapped within their apartments and homes — both part of the university experience but feeling marooned outside it. Our hope was to create a collective space for our community to come together, to share their experiences, their struggles and the things they have held on to in this uncertain time.

When historians 100 years from now look back at 2020, what do you think will stand out? What do you hope will have come from it?

Berry: I hope that people will have a deeper understanding of how the UT community experienced 2020. As you can see, what people shared was very personal responses to the changes around them, and this project offers primary documents to make sense of this important year.

Clulow: It’s difficult to predict this. The one thing I know for sure is that 2020 will be studied for decades and indeed centuries to come. We hope our site will be a resource for this, but even more important for us was our goal to create a collective online space where we could all come together.

2020 is over, but the project continues, and you talk about “the Long 2020” on the site. What prompted you to keep collecting stories and photos?

Berry: Yes, 2020 is over but the ramifications of what happened that year will impact us for years to come. For example, the pandemic is not over, many of us are still wearing masks and the world still faces a global health crisis. The fight for social justice continues as organizations, institutions and communities look for equity and healing. So it’s difficult to determine when we should stop collecting time capsules. Given that we see this as an outlet for expression, we hope that it will continue until people refrain from submissions.