Beyond the scaffolding and construction, the Blanton Museum of Art is still open.

The museum grounds are being transformed outside, but inside, red velvet curtains conceal the Sarah and Ernest Butler Gallery, nestled in the column-lined portico of the central auditorium. On display is Rosario I. Granados’ most ambitious exhibition since she accepted the position of Marilynn Thoma Associate Curator, Art of the Spanish Americas in 2016.

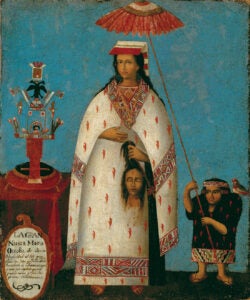

The Blanton’s latest exhibition, “Painted Cloth: Fashion and Ritual in Colonial Latin America,” houses paintings in gilded frames, sculptures, and tapestries from 15th through 19th century Latin America. The art pieces are part of a loan program between Texas and the institutions and archives of Spain, Mexico and Peru. They will be on display until Jan. 8, 2023.

“I feel that I have been in labor for the past two weeks. And now this is the christening of this exhibition,” Granados says.

Granados and colleague Carter Foster, deputy director for curatorial affairs at the Blanton, gave a brief introduction on Aug. 12 to 15 note-taking writers and journalists who would see the almost-finished exhibition before public release on Aug. 14.

“This was a huge undertaking for the Blanton,” Foster says. Granados has “been working on this exhibition for four years — which is the amount of time it takes to do really ambitious scholarly shows.”

Both Foster and Granados feel it’s fitting to have these items on loan in Austin because of Texas’ brief history under the colonial Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1690 to 1821.

“All these objects function as cultural ambassadors,” Granados says. “We have such a great population of Latino people in Texas and Austin, in particular, so I thought it was the best way of attracting that community, but I also wanted a universal topic so other people could come see these objects and find a relationship to them.”

Granados reveals the quiet gallery behind the red curtains; the temperate, dim space insulates the exhibition from the echoes of the auditorium. The gallery walls are deep aubergine and forest green, enhancing the colonial era palette. Granados says galleries that showcase colonial art traditionally use a royal red backdrop to mimic the cochineal-dyed garments worn by cardinals of the Spanish royal church. She decided to go against the norm. The complementary shades of green and purple allow the painted fabrics to step off the canvas as focal elements of the exhibition.

The cloth and textiles indicate change, cultural evolution and the racial mixing of peoples in Spanish-speaking Latin America. Colonial Spanish art is also politically contentious due to the overarching story of violence. Granados says that the show does not explicitly tell viewers how history unfolded. Instead, she encourages guests to participate in art interpretation through critical thinking.

Granados extracted the theme of fashion and ritual from the collection of objects in order to reach a wider audience and expose the history of diversity in Latin America.

“I wanted to find a universal topic that would allow other people to come and see these objects,” Granados says. “Fashion and ritual … it’s how (we’re) perceived by others and how we build our persona. I thought it was a fashionable way to attract people to the art of Spanish Latin America.”