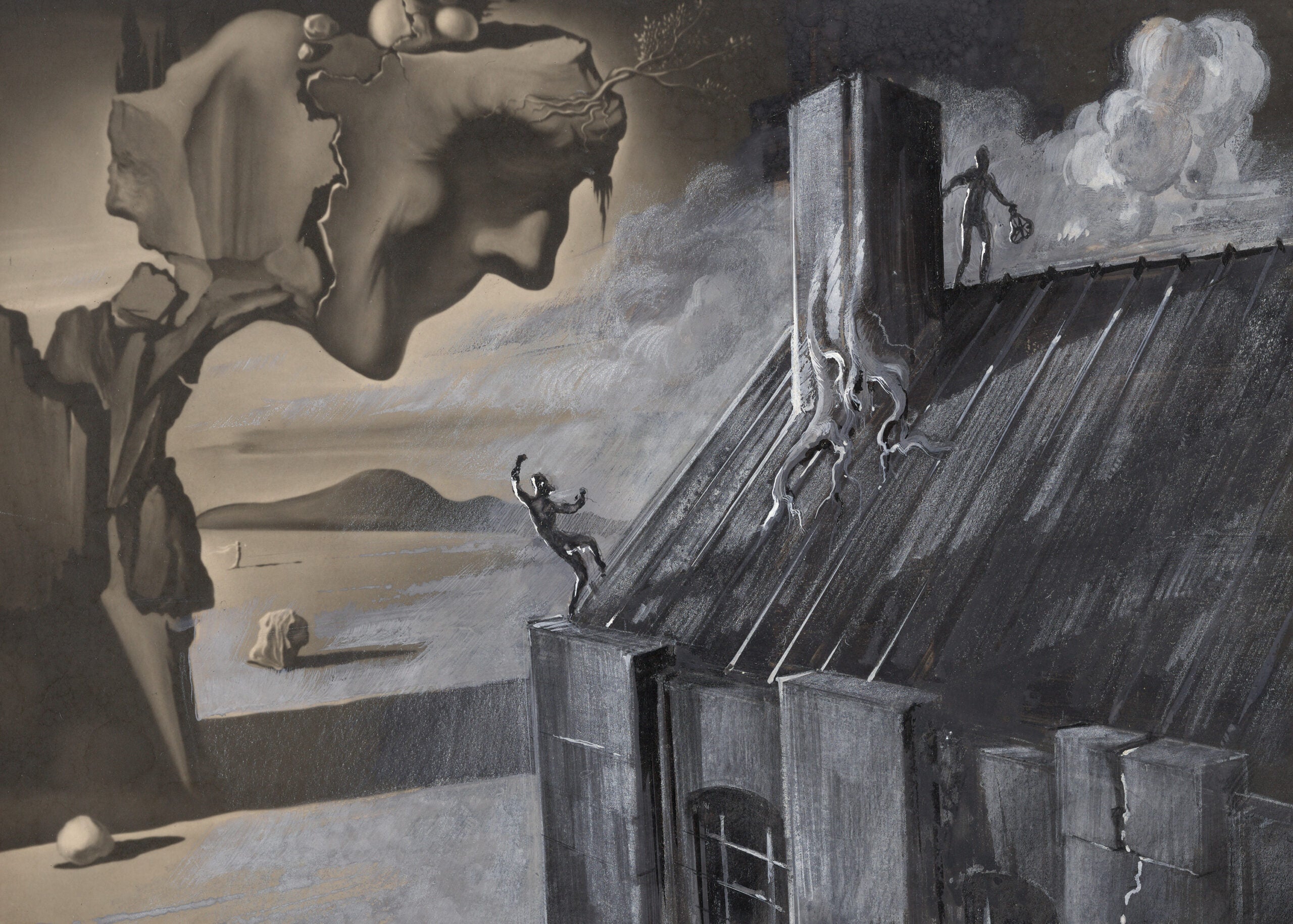

Film experts and casual movie enthusiasts alike have a new exhibition to browse through at the Harry Ransom Center. “Drawing the Motion Picture,” which is free to the public and open until July 16, aims to educate visitors about how the creative visions of writers, directors and artists come to life in film.

Walking through more than a century of movie history, visitors can pore over hundreds of concept art pieces, storyboards, scripts, set designs and other items dating back to the silent film era. The displays feature a wide array of notable works ranging from dramatic Golden Age classics such as “Lawrence of Arabia” and “West Side Story” to ’80s sci-fi tales such as “Return of the Jedi” and “E. T. the Extra-Terrestrial.”

“I think it’s a good representation of the Ransom Center’s film collection,” says Steve Wilson, the Ransom Center’s Robert De Niro curator of film. “Just about every collection in the Ransom Center’s film collection includes some kind of production art for film, so I’ve been really happy with how that’s worked out.”

Highlights from the exhibition include storyboards from the climax of “Rebel Without a Cause” and the Sugar Ray Robinson fight in “Raging Bull” — accompanied with Robert De Niro’s handwritten notes. Another large display illustrates how the special effects were done in a key scene of “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids.”

“This is the scene where the kid is in the bowl of Cheerios, and he’s about to be eaten,” Wilson says. “There’s quite a few wonderful, wonderful pieces in the show.”

Aside from narrowing down the items and preserving their integrity, locating enough material for an exhibition like this one comes with unique challenges. Wilson says this is because production art is considered “disposable.” Many of the pieces were saved by individuals, and Wilson pulled from the personal collections of Robert De Niro and David O. Selznick, among others. One example is a painting that the production designer of “Lawrence of Arabia” gifted to Peter O’Toole, who then carried it around for decades before it ended up at the Ransom Center.

“That’s how it survives,” Wilsons says. “And we have other examples like that, that were given as mementos, and people kept them. … But a lot of storyboards and production art don’t survive because their use is finished when the film is finished.”

Wilson says he hopes the exhibition will prompt visitors to think about the roles that production art plays in filmmaking. In the three decades he has worked at the Ransom Center, Wilson realized he needed to bring some of the film collections’ “evocative images” to light.

“I think we can get a deeper understanding of not only how the movies were made, but of the films themselves,” Wilson says. “What did they mean? What were the filmmakers trying to accomplish in making their film? These drawings and paintings, I think, give us a lot of information about that.”