At the glassy blue waters’ edge of Greenland’s fjords sits the world’s second-largest ice sheet measuring between 6,600 and 9,800 feet thick and covering 660,000 square miles. The ice is contained by coastal mountains and flows outward to the ocean like a jagged mythological creature — both beautiful and unrelenting to what lies in its path.

According to the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado Boulder, the 2022 melt season in Greenland — between April 1 and Oct. 31 — saw the 19th-highest melt rate in a 43-year satellite record.

In the wake of climate change, the annual net loss of ice worldwide is increasing faster rate than the ice sheets are regenerating and advancing. But in observation, sites at the glaciers’ edges in three of Greenland’s fjords vary in behavior. For example, Kangilliup Sermia’s retreat is minor, Umiammakku Sermiat’s retreat is rapid, and Kangerlussuup Sermia is still relatively unaffected. The lack of uniformity in melting poses new questions for scientists. More accurate answers to these questions require a team of experts and a submersible robot to go into uncharted territory beneath the ice.

“The overall climate might say everything’s going to retreat, and eventually it will. But the local details of what’s happening can be much more complicated,” says Sean Gulick, a marine geophysicist at the Jackson School of Geosciences. “(We hypothesize) that the sediment matters … can potentially mitigate climate change for a given ice system (for a while).”

This expedition is really exciting. And it’s very high reward, but also very high risk.

At the Jackson School of Geosciences, UT’s only faculty glaciologist, Ginny Catania, first submitted the research proposal to the W. M. Keck Foundation with colleague Tim Bartholomaus from the University of Idaho in 2017.

The proposal aimed to secure $1.5 million in funding for the expedition, including the acquisition of the submersible remotely operated vehicle, the ship, its crew and the field technicians to operate equipment. The Keck Foundation supports high-risk scientific, engineering and medical research for potentially transformational findings that benefit humanity. Within that budget, the science and interpretation of data will be conducted pro bono.

In December 2022, Catania and Bartholomaus were awarded the Keck funding. “I felt like I had won the Miss America pageant,” Catania says. The money solidified the expedition and set concrete plans into motion.

Catania and Gulick are part of a team of experts at UT, including Benjamin Keisling, John Goff, Marcy Davis and Dan Duncan, studying the morainal banks beneath the glaciers to better understand how sedimental mounts stabilize and insulate the glaciers. Morainal banks may be largely responsible for the rate of melt because they create a buffer system against the warming ocean water. Gulick says that with this information, there may be opportunities to build bigger banks and help mitigate melt rates in the short term.

“The climate system (the ocean and the atmosphere) matters, obviously, to the ice sheets, but the topography, the geometry … has a first-order effect on how the ice is going to respond to climate,” Catania says. “You can think about the climate pushing an ice sheet into a new state, but the topography controls how much change happens.”

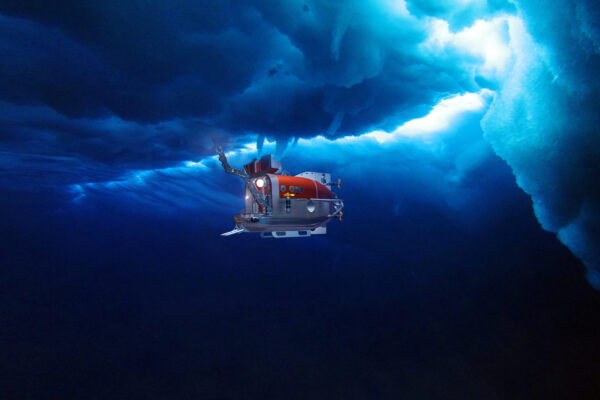

In late summer 2024, the team will travel with the crew of a ship called the RV Celtic Explorer and a cohort of engineers, including Davis and Duncan, and technicians who will operate a robot called the Nereid Under Ice (NUI). They will work 24 hours a day in shifts, collecting data with the NUI, designed and engineered at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts under the expertise and supervision of engineer Mike Jakuba.

“This expedition is really exciting. And it’s very high reward, but also very high risk. I mean, we’re going into an environment that no one has really tried to fly a vehicle in before,” Jakuba says.

The NUI is bright orange and shaped like a brick with rounded corners. The front doors streamline the nose to reduce drag as it ventures in the water beneath the ice. The vehicle communicates with the operators on the ship via a fiber-optic tether three times the thickness of a human hair. The cable allows the NUI to move up to 10 miles from the ship using power from battery packs stored within its frame. Jakuba says one of the main challenges of driving a vehicle under the ice is the limited battery life. In addition, while the seafloor is stagnant, the ice is in flux. NUI and the ship constantly adjust their locations to navigate with the ice’s movement, so retrieval is often the most significant risk in a day’s work. If the fiber fails, the pilots can direct NUI to a pickup location using underwater acoustics — as long as the ice doesn’t block it.

“On one of our display screens, we have this circle, the circle of doom, that slowly closes in on you as your battery goes down,” Jakuba says. “(At that moment) we need to get the robot back to the vessel, and the vessel could be drifting away. We have to manage this to get the vehicle back constantly.”

The second risk to the NUI’s survival beneath the ice is the plumes of rapidly moving freshwater and sediment from the surface of the ice sheet to the seafloor. They emit water at a rate of several meters per second, and the NUI will not survive if it is caught in the currents. However, Jakuba says they’ve prepared NUI to avoid these plumes with sensors that detect currents.

NUI’s mobility mechanisms include thrusters, a navigation system, lights and cameras. It takes images of the seafloor, collects rock and sediment samples with a robotic arm, and captures fluid from the glacial plumes (at a distance), allowing scientists to see how much sediment moves through the melting process and how much melting contributes to the building of morainal banks.

For the team at the Jackson School of Geosciences, acquiring the NUI and venturing into new territory is more than a personal or professional pipe dream. Being awarded access to this robot puts UT researchers at the cutting edge of global discussions on climate change and more accurate predictions on the timeline for sea level rise.

“Greenland can give us 23 feet of sea level rise. Antarctica can give us 197 feet of sea level rise. So it’s a large problem,” Catania says. “And we’re seeing that there’s this big spread from Greenland alone, so Greenland is probably going to contribute the most.”

Catania doesn’t know precisely why glaciers captivated her. “I’m from Canada,” she says laughing. “Which doesn’t really mean anything. There are lots of people from Canada who don’t study glaciers. But I was drawn to them as an undergrad.”

Catania studied mathematics at the University of Western Ontario. While an undergraduate, she felt a stronger connection to the science community on campus, so Catania decided to apply mathematics to scientific topics and began to see how equations could describe natural processes and phenomena such as ice flows and, subsequently, any fluid on the planet. Catania later moved to Texas after earning her Ph.D. in geophysics from the University of Washington.

While she lives far from any coastal or oceanic ice, life in Texas tethers her to coastal communities most vulnerable to sea level rise. The findings of this expedition will speak directly to the effects of glacial melting on the Gulf Coast and the Caribbean islands in a more accurate, nuanced way.

Catania says that because the current models assume the ground below the glaciers is stagnant, the estimated range of sea level rise within the science community is anywhere between 5 and 33 centimeters (2 and 13 inches) by 2100.

During an expedition to Alaska, Catania found the topography beneath the ice changed 26 feet in just over one year. Without this information for Greenland, the models have major holes. Every time a moraine is mapped on the seafloor, the scientists can see just how far the ice has advanced and what happened to the ground beneath it during that process. Taking a core sample helps explain the timeline of that process.

“We have three different glaciers that are of different sizes and are generating different scales of morainal banks. They all come from the same source part of the ice sheet — so we need to consider the influence of these sedimentary processes,” Gulick says.

In Catania’s mind, the lack of understanding around this variability means science is missing crucial components that could help more accurately predict the timing of sea level rise and subsequently alert coastal communities for future planning.

Keisling is the expedition’s lead modeler. He’s been on top of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. During his career, he has extracted numerous core samples — essentially large plastic pipe-looking tubes that penetrate ice and the sediment below. Their contents tell a geological history of the ice sheets. Through that history, Keisling is beginning to understand the bigger picture of how glaciers have advanced and retreated before satellite records existed. Geological time mapping provides insight into how the current retreats function differently from the retreats of more stable periods in the ice sheets’ life spans. Keisling will be aboard the ship putting the data that NUI collects into his model.

“When you see images and videos that have become more widespread in popular understandings of climate change, there’s a duality to it,” Keisling says. “One, there’s a recognition that there’s a natural process appreciated separate from human influence — irreversible on human time scales. And then there’s the representation of human activity that is out of balance.”

Catania is now working to receive additional funding from the National Science Foundation to support all the volunteers for the expedition and to forge a national and international alliance with other glaciologists and sedimentologists, bringing as many global experts on deck as possible.

“We’re part of something important, but we’re not the linchpin in making this entirely better, right?” Catania says. “We’re hoping that we can illuminate what might be important about this process and where it might need to be included in the global discussion.”