In a childhood memory, David Hillis recalls the time when the woodlands of Lwiro in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo were unexpectedly pleasant. The region, where the moisture in the air intermingles with the sweat on one’s skin moments after stepping outside, is infamously steamy and tropical.

On that day Hillis walked among delicate flowers with vibrant greens surrounding him on his way to school. He stumbled across a thick spider web — big enough to catch a bird, which he later discovered was what the spider intended to do. Hillis says he was fascinated by sights like these. He began carrying a camera and would momentarily lose track of time as he took snapshots of the curious nature around him. Hillis is now the director of the UT Biodiversity Center, a professor in the Department of Integrative Biology, and the holder of Alfred W. Roark Centennial Professorship in Natural Sciences.

Hillis’ father was a viral epidemiologist. His work took his family to many countries in Africa and throughout parts of India. Hillis spent much of his childhood exposed to wide ranges of biodiversity.

“Well, while in Africa and India, the main way I entertained myself was to go outside and catch things all over the world,” he says. “And so I always felt excited about animals and nature.”

After moving back to the United States, his family lived in Texas, Louisiana, Florida and Maryland. Eventually, Hillis attended Baylor University, where he received a bachelor’s degree in biology, and later the University of Kansas, where he earned his master’s of science, master’s of philosophy and doctorate in biological science, specializing in molecular evolution and systematics.

On April 11, Hillis’ book “Armadillos to Ziziphus: A Naturalist in the Texas Hill Country” was published, capturing his youthful curiosity and love of nature, years of study, and appreciation for the Hill Country.

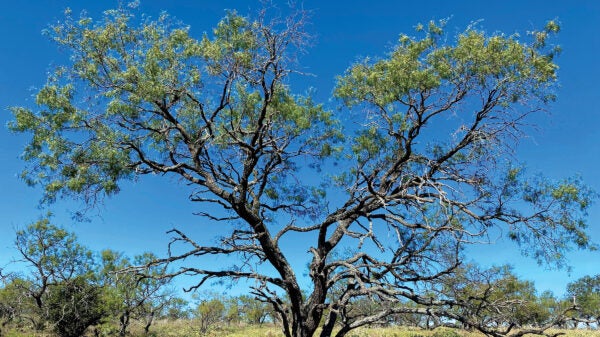

In the mid-1990s, Hillis and his wife bought a ranch, now coined Double Helix, in Mason County. On his land, he ensures the plant life he cultivates is conducive for native animals, whether it’s the average deer or declining fireflies. Lotebush, a spiny clumplike shrub, is a common plant removed by home and ranch owners, but to Hillis it is very important because it provides shelter for ground-dwelling quail.

“I’ve always loved the land, and I wanted to work it, restore it and protect it,” he says. “It’s just a very attractive place that seems like home to me.”

Hillis wrote the book hoping to get readers to understand the true beauty of the Texas Hill Country, which not only contains clear, spring-fed creeks and colorful pockets of wildflowers but is also a biodiversity hot spot, with many species found only there.

“I try to convince landowners that actually keeping a few of these (plants) around in your pastures is a really good idea and helps your wildlife,” Hillis says. “It also, I hope, helps people appreciate some underappreciated Texas plants.”

Down the road from the Double Helix is Rancho Cascabel — Rattlesnake Ranch — owned by longtime friend Harry W. Greene. Hillis and Greene met when Hillis was applying for graduate school and Greene was a new faculty member at the University of California, Berkeley.

Down the road from the Double Helix is Rancho Cascabel — Rattlesnake Ranch — owned by longtime friend Harry W. Greene. Hillis and Greene met when Hillis was applying for graduate school and Greene was a new faculty member at the University of California, Berkeley.

Though Hillis did not attend Cal, the two stayed in touch throughout the years. Once or twice a year Greene would come down to Hillis’ ranch, and they would herd his longhorns and hunt deer. After Greene’s wife got a job at UT, he decided to buy his own ranch, and today the two nature lovers live a hop, skip and a jump from each other.

Hillis is a steward of 700 acres. Up to 48 head of cattle graze the diverse grasses on his ranch. When Greene officially bought his ranch, Hillis’ gifted him with a housewarming longhorn.

“We’ve just become ever-closer friends with lots of overlapping interests in science and nature and ranching and rural people and how to make it all come together for a better tomorrow for everybody,” Greene says.

Hillis describes the Hill Country as a crossroads between the southern edges of North America and Mexico. Central Texas is the gateway to the North American grasslands.

“The Texas Hill Country has always been a real draw,” Hillis says. “For me, it’s one of the reasons I really wanted to be at the University of Texas. It’s a beautiful, natural place.”

OTHER WORKS

Notable publications by staff and faculty members

Pitching Democracy: Baseball and Politics in the Dominican Republic

By April Yoder

From Juan Marichal and Pedro Martínez to Albert Pujols and Juan Soto, Dominicans have long been among Major League Baseball’s best. How did this small Caribbean nation become a hothouse of baseball talent? April Yoder traces how baseball has empowered Dominicans in their struggles for democracy and social justice.

Selling Science Fiction Cinema: Making and Marketing a Genre

By J. P. Telotte

For Hollywood, the golden age of science fiction was also an age of anxiety. Amid rising competition, fluid audience habits, and increasing government regulation, studios of the 1950s struggled to make and sell the kinds of films that once were surefire winners. Telotte uses such films as “The Thing From Another World,” “Forbidden Planet,” and “The Blob,” to explore the shifting ways in which the industry reframed the SF genre to market to no-longer static audience expectations.

Quantum Criminals: Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors From the Songs of Steely Dan

By Alex Pappademas and Joan LeMay

Steely Dan’s songs are exercises in fictional world- building. No one else in the classic-rock canon has conjured a more vivid cast of rogues and heroes, creeps and schmucks, lovers and dreamers, and cold-blooded operators — or imbued their characters with so much humanity. “Quantum Criminals” presents the world of Steely Dan as it has never been seen, much less heard.

Channeling Knowledges: Water and Afro-Diasporic Spirits in Latinx and Caribbean Worlds

By Rebeca L. Hey-Colón

Water is often tasked with upholding division through the imposition of geopolitical borders. We see this in the construction of the Rio Grande/Río Bravo on the U.S.-Mexico border, as well as in how the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean are used to delineate the limits of U.S. territory. In stark contrast to this divisive view, Afro-diasporic religions conceive of water as a place of connection; it is where spiritual entities and ancestors reside, and where knowledge awaits.

Recommend a book at pitch@texasconnect.utexas.edu.