UT prides itself on housing countless archives, collections and heirlooms. Some are carefully stored in dimly lit and climate-controlled rooms, preserved by caretakers; others are housed in classrooms, ready to serve eager students in their academic endeavors. And some are proudly on display like prized jewels. UT is full of hidden treasures — one just needs to know where to look.

The Rob Roy Kelly American Wood Type Collection

In the sun-soaked Design Lab of the Art Building, students sprawl at wooden tables, sketching, carving and perfecting their projects. The cranks and squeaks of the decades-old printing presses in the back echo throughout the room. Next to dozens of design books and handwritten notes and doodles from students, 166 labeled cardboard boxes span an entire wall. Inside each box are centuries-old wood typeface blocks stretching from De Vinne Italic to Tuscan Egyptian.

The Rob Roy Kelly American Wood Type Collection archives thousands of vintage blocks used for letterpress beginning in the 1800s. They were collected and cataloged by design historian and scholar Robert Kelly for the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in the 1950s.

Kelly began his efforts when he saw this type being thrown in the trash as new technology, such as dot matrix and laser printing, pushed its way into the spotlight. He wanted to preserve this history and create a resource to educate his students. He eventually sold the collection to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, which later sold it to the Ransom Center, where it stayed through the early 1970s. In the ‘90s, the collection was given to the School of Design and Creative Technologies in the College of Fine Arts, where it is now used by students almost daily.

“A big part of my work has been to connect the dots,” says Henry Smith, fabrication manager and caretaker of the collection. “And that makes it easy for students to use this collection and keep it relevant. Because it’s so special that we get to have this here. We’re very lucky to be able to be hands-on with artifacts like this.”

All design students are required to take typography classes where they will complete at least one type exercise using the collection. Smith encourages the students to reframe how they think about graphic design and step away from computers to work with the letterpress — imperfections, frustration and all. He jokes that some students don’t appreciate these challenges as much.

“I like to frame the collection now as embracing that history and the things that are not perfect about it,” Smith says. “Using letterpress is a way to have a collaboration with the technology.”

Students learn how the wooden type blocks forced designers to make certain choices and what analogue skills were necessary before digital technology came along. For example, the placement of the block and its correct interaction with the letterpress could determine whether a job is well done or is in need of a do-over. By interacting with these items, students learn how far their craft has come.

Smith says that using this collection helps students think about how letterpress is still relevant and provides awareness of how the design industry has grown past some of the problematic aspects of its history.

“It’s an effort to bring a new generation of designers into a process of thinking about what this collection is and what it means,” Smith says. “I don’t need to be a gatekeeper of this; it belongs to everybody. And I want to figure out how to help a new diverse group of creatives embrace it.”

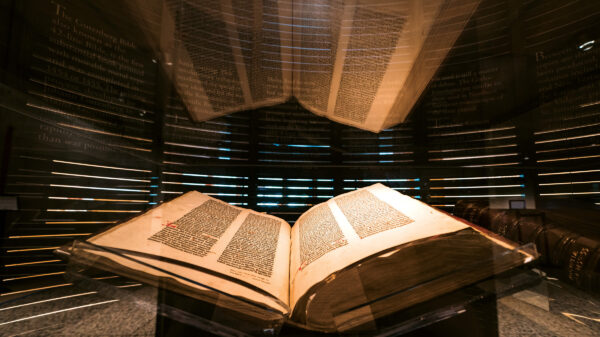

Gutenberg Bible

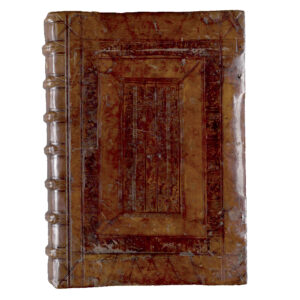

In the entryway of the Harry Ransom Center, the Gutenberg Bible exhibit greets visitors. The two massive, leather-bound volumes sit enclosed in glass, haloed by dim lighting. Separated from the rest of the lobby, the exhibit is a quiet place to marvel at the ornate 600-year-old piece of history.

The Ransom Center’s copy is one of 20 complete, surviving copies from the original 150-plus Bibles written in Latin. German inventor Johannes Gutenberg and his team of printers published their collection in the mid-15th century. It is often heralded as the first substantial book printed with movable type in Europe.

The university purchased a copy for $2.4 million dollars in 1978, a million of which was raised through small donations. In 1983, for the centenary of the university, Sally Leach, assistant to the director of the Ransom Center, and Karen Gould, a medieval art historian, took one volume of the Bible on tour to 18 different cities in Texas.

“In some ways, it was kind of this synecdoche for the university,” says Aaron Pratt, who is the Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Curator of Early Books and Manuscripts at the Center. “The university was like: ‘We have made it. We’ve had 100 years.’ The Bible was the public face of that monumental moment in 1983.”

The Ransom Center prides itself on its modern literary archives, but the Gutenberg is what it’s best known for internationally. This investment helped put the university on the map, with the purchase being the most recent and most expensive of any of the Gutenbergs.

“The Gutenberg Bible is the first thing you see when you come into the (Center), right?” Pratt says. “It’s had this kind of outsized role even in the life of the university.”

The Bible, which is believed to have been used by a group of Carthusian monks as their lectionary Bible, is riddled with markings and handwritten corrections, as well as the original illuminations and decorations. It is also one of the most complete copies available.

“Our copy helps raise a lot of research questions that are still in the process of being answered,” Pratt says. “That’s one of the main reasons why we went after this particular copy, because it’s strange.”

Pratt believes the Bible also has a lot of value for broader pedagogical questions about innovation — beyond academics’ questions of who owned the Bible originally or about the initial printing process created by Gutenberg.

“It seems very clear that there were iterations and improvements and changes to the way that printing happened in the decade that immediately followed Gutenberg,” Pratt says. “I find it really exciting and interesting because it helps people sort of think through both how we do work as historians and also how innovation and technology work.”

Knopf Papers

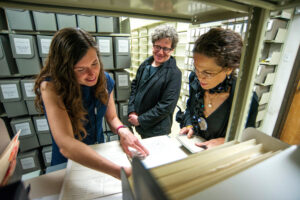

Tucked away in a windowless room on the fifth floor of the Ransom Center, 1,500 file boxes filled with artwork, correspondences and reviews from the Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. publishing company await eager archivists and aspiring writers. Knopf Inc., which began in 1915, is one of the nation’s well-known publishers of distinguished fiction and nonfiction literature.

With records beginning in 1945, the papers are one of the many collections available to pull and study in the Center’s reading rooms.

“The Ransom Center is very well known for its literary archives,” says Megan Barnard, associate director for acquisitions and administration. “But people may not be as familiar with the fact that we have a number of really important publishing collections. … You can learn a lot about the history of the Knopf publishing firm itself and also about many of the individual books that they published or authors they worked with.”

After learning about Harry Ransom’s efforts to build archives at the University of Texas, Knopf Inc. donated a significant cache of documents between famous writers, editors and the publishers. Today it remains one of the most popular and sought-after collections housed deep within the Center’s stacks. In the past 10 years, it has been in the top five most frequently used of the Ransom Center’s thousands of collections. Barnard says she always enjoys hearing what researchers are discovering with the materials; she then suggests where to look next.

“(That’s why it’s really important) for each individual to connect personally with these items … discover about our culture (and) why people make the decisions they make. We can learn and grow from them,” Barnard says.

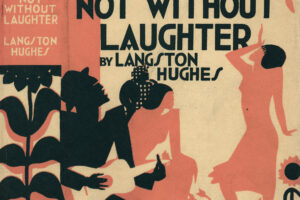

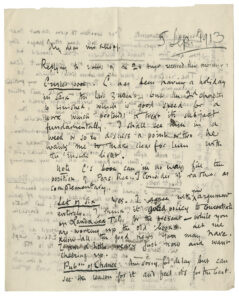

Amid the innumerable yellowing typewritten pages from the likes of Doris Lessing, Langston Hughes and even Julia Child is correspondence that gives a sense of the negotiations, edits and rewrites involved with publishing. The documents recount the honest, arduous process of editing that lifted these celebrated literary works out of obscurity and into public view. Researchers use them to make connections to the authors they are studying.

Students of the archives also uncover universal lessons of patience and persistence. They witness negotiations and expectations from both writers and publishers. A reader’s report from two of Knopf’s editors contains a page and a half of detailed criticisms rejecting a book that eventually became Jack Keroauc’s “On the Road.”

“This is something that’s really helpful for young writers and students,” Barnard says. “(They get) to see something that has become this real cultural touchstone that didn’t have an easy beginning and to know that not every book was published as quickly as one might think.”

One of the best aspects of working with the archive is helping students, faculty and others discover something new about literature and publishing, she says. “Finding ways to better understand our cultural moments and finding ways to make those accessible to other people is incredibly rewarding,” Barnard says.