Lady Bird Johnson traveled through the South in 1964 to garner support for her husband’s Civil Rights Act. She opted to travel by train in order to visit more rural areas. The long, winding journey allowed her to observe the land closely. She was irked by the presence of monocropping, which homogenized the fields and destroyed biodiversity throughout the Southern landscape.

Johnson and actress Helen Hayes established the National Wildflower Research Center — now the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center at 4801 La Crosse Ave. in South Austin — in 1982 to improve native biodiversity and conservation.

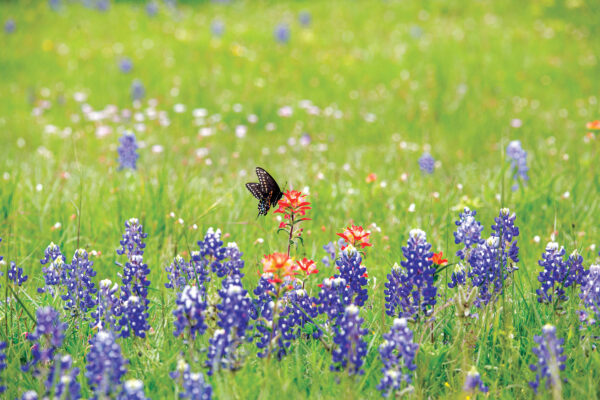

In the spring, blankets of bluebonnets are everywhere, cascading out and over the edges of flower beds and filling open fields. Occasionally, the sea of purple is interrupted by a cluster of vibrant red Indian paintbrushes.

In late March and April, the state flower lures droves of visitors hoping to catch that perfect Instagrammable photo, and individuals, children and families submerge themselves in flora during the short, robust blooming season.

“Of course, we’ve got our state flower, the bluebonnet, everywhere,” says Dawn Hewitt, director of operations at the center. “But I love a little bit later in the year in late spring and into summer, when we have the firewheels.”

To encourage more comprehensive knowledge of native plants and flowers, the center began selecting a wildflower of the year. This year, it chose the mealy blue sage. Despite its name, the plant is elegant, with thin, tall stems supporting its many small blue flowers reminiscent of lavender. The mealy blue sage blooms from midspring to October, drawing visitors after the early spring bloom of bluebonnets and pink buttercups.

In addition to showcasing the native landscape, the center hosts installations and activities throughout the year. Its current exhibition, “Seeing the Invisible,” is an augmented reality experience that allows visitors to explore famous artists’ monumental sculptures in the fields without harming or physically altering the greenery. Last fall, the center invited Bruce Munro to install his “Field of Light,” which illuminated the rolling hills with colorful solar-powered LED orbs and glowing wires — like a scene from the film “Avatar.” The center’s annual exhibit “Fortlandia” reopens Sept. 30 and runs through January 2024. “Fortlandia” features local artists, landscape architects and designers, who build temporary creative structures that kindle a sense of play in children and evoke nostalgia in adults.

“I’m always kind of looking for things that are new and might entice someone who maybe doesn’t see themselves as a gardener,” Hewitt says. “Having that connection to nature is so important for people. And I think, ultimately, having a healthy ecosystem impacts us all. Mrs. Johnson said, ‘The environment is where we all meet.’”