The year is sometime between 1945 and 1952. Japan is under U.S. occupation. A new bureaucrat has been appointed as a censor, and already he has a complaint. A woman is angry that her first-person account of the atomic bombing at Hiroshima is being denied publication. The rules say there can be no literature about the atomic bomb unless it’s scientific. Now, though, the Japanese author is being harassed by U.S. intelligence officers. The censor didn’t know their denial would lead to this.

“The Censor’s Desk” immerses players in the time period and allows them to feel the character’s pains and frustrations. By deeply engaging the learner, a video game such as this can draw students in more than an informational presentation or textbook would, associate professor Kirsten Cather says.

“This is one of those kind of more somber, serious episodes in the game, where we try to think through the repercussions of censorship by putting the player in the shoes of a censor,” she says.

Cather has been teaching in the Department of Asian Studies for 19 years, serving for the past four years as the director of the Center for East Asian Studies. The center is home to JapanLab, a program that generates Japan-focused educational video games and digital humanities projects. JapanLab is a collaboration between the Department of History and the Department of Asian Studies, with funding from the Japan Foundation, which promotes cultural exchange, and the College of Liberal Arts. Cather is a JapanLab director alongside professors Adam Clulow and Mark Ravina in the Department of History.

They want to make something that they’re proud of and that can be widely used by students for years to come.

Each semester, JapanLab student teams create entirely new projects. They work alongside a faculty member such as Cather or a postdoctoral fellow specially recruited for the program. Teams are given 15 weeks to develop projects, with each student taking the lead on coding, sound, art, narrative, research or user experience.

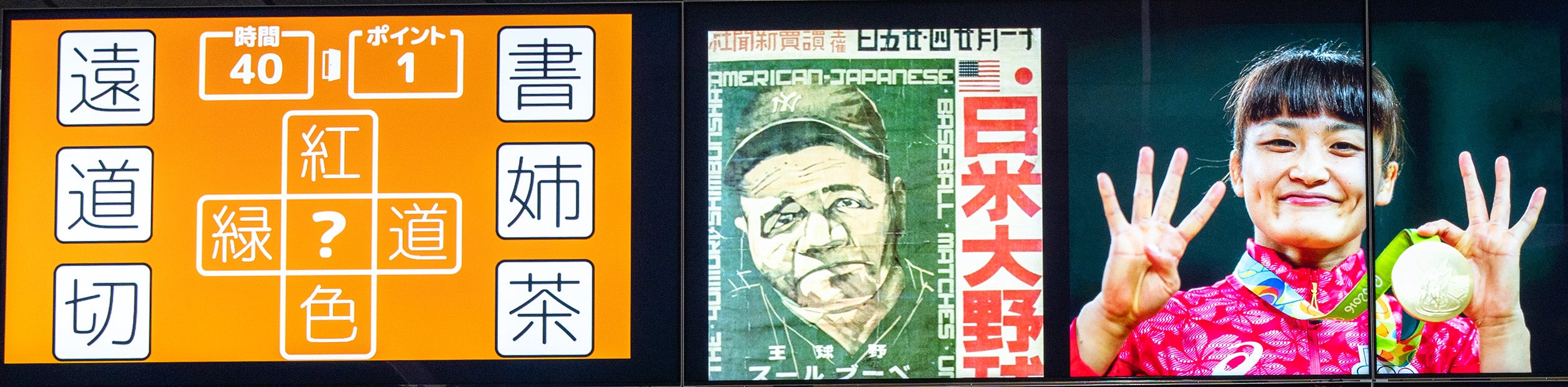

In “The Censor’s Desk,” using an approve or deny stamp, the gamer must inhabit the role of the censor, interpreting the rules while analyzing authentic texts that were produced at the time by Japanese writers. In-game consequences relate to real-world outcomes and allow players to analyze the profound ripple effects of artistic texts in society.

The game spans several decades, from the Meiji period in 1868 to the formation of a new constitution, to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the occupation period. To indicate when a gamer enters a new time period, the game artists included details such as placing an American flag in the interview room alongside the Japanese one during the occupation.

The game eventually will be freely available on gaming platforms such as Twitch and Steam. Cather says that seeing the game in the classroom is the thing she is most excited about.

“The best part of this game is that it’s rigorously researched. It’s responsible,” Cather says. “At every turn, students have to think about how to make this interesting, digestible and playable as a game.”

The JapanLab website contains a variety of completed projects, from what Cather calls “extensive, incredible timelines” to visual novel video games. Some students have created digital versions of classic Japanese board games with historical commentary.

Cather says none of this would have been possible without the support of the College of Liberal Arts and the Japan Foundation grant.

“The Japan Foundation is a Japanese government organization that helps promote Japanese studies outside of Japan,” Cather says. “It is wonderful that they invested in us because this program is very new. Adam Clulow started this pilot program, and it worked so well that we decided to try this out on a bigger scale.”

At the end of each semester, JapanLab holds an expo so student teams can demo their games. Industry professionals such as Clay Carmouche, a former Xbox narrative director who now works with Brass Lion Entertainment, talk with students, preview their games and spend the day with them, allowing the students to gain knowledge on what it’s like to work in the video game industry.

“When we started talking about what’s the value of this, we really believed that this kind of experiential learning is crucial,” Cather says of working with Clulow and Ravina. “What we’re finding is that students pour so much energy into it because they are creating something. They want to make something that they’re proud of and that can be widely used by students for years to come.”