Spending time in the sands, immersing herself in a world of ceramics and ancient pottery at an archaeological dig site — for 12 years, this is how Stephennie Mulder spent her summers. Until 2010, she traveled back and forth to Syria with the cooperation of the Syrian antiquities authority, spending six weeks a year as the ceramics expert at a site that dates to the Bronze Age and was occupied until the 13th century.

More people will be able to learn about the past buried in the sands of the Middle East thanks to an open-world video game that Mulder and her colleagues are developing.

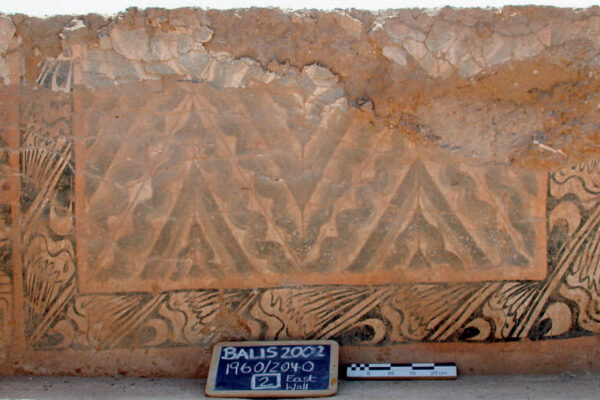

Mulder, an associate professor of Islamic art and architecture, is working on a multivolume publication on excavated ceramics, and as a side project, she applied for the Bold Inquiry Incubator grant from the University with a proposal to develop a 3D interactive digital game based on the excavation of an early Islamic palace in Syria. After receiving the grant, she teamed with two faculty members from the School of Design and Creative Technologies: Jessie Contour for game development and Kate Catterall for game design.

“We’re going to tell the story through the eyes of a young girl or boy, who is maybe like 10 to 11 years old, who is observing these events as they unfold inside this castle,” Mulder says. “On the way, she will encounter a lot of different characters who will walk her through this story, who will tell her what’s going on in the outside world and enable her to explore the world.”

The dig site where Mulder worked was one of the places where the first dynasty that ruled Syria built a little castle. It was inhabited by one of the princes in the royal family, and this castle that Mulder encountered in real life will be at the center of the digital landscape of the game.

“In 750, this earliest dynasty of Islam was overthrown by another dynasty who came from the east, centered in what is today eastern Iran. They gathered followers and eventually had an uprising,” Mulder says. “We’ve decided to set the story right at that moment of transition when there’s this kind of rising tension and rumors of war coming from the east, but it hasn’t yet landed in this little castle.”

Mulder says that using a popular medium to teach a historical story feels very natural, especially with the growth of virtual reality. The game design will be stylized with photorealistic elements for the visual aesthetic to be harmonious with the time period the game is representing.

“I realized that people are learning history from the media, and whether we like it or not, that is how people are learning now,” Mulder says. “Historians have a responsibility to make sure that those stories are truthful, and that they’re portraying the past and all of its complexity and diversity.”

Catterall is working on the design and visual aspects in the game and found it a fascinating concept to be able to “flash back and forth through time” through the objects found in the game.

“There’s this wonderful piece of ceramic from China, but it was found at this location because this location was a major intersection on trade routes,” the associate professor of design says. “The idea is somebody contemporarily stepping down and picking up a fragment of a piece of Chinese pottery, and then the whole environment coming alive with what used to be a port.”

Catterall doesn’t view the project as just a game but as a journey of discovery for the player.

“The challenge is to find things, ask the right questions, make connections, and be able to travel through time,” Catterall says.

Contour, an assistant professor of practice in arts and entertainment technologies, is using Unity as the game engine. When playing the game, “the player gets to embody the role of a character by taking on their goals and ambitions related to the character,” she says, and this in turn allows them to connect to the story in a deeper way and explore at their own pace.

“The system that I have already kind of started setting up involves creating a little character that can run around and look at different things and a system where they can go up to another character or an object and have information showing on the screen,” Contour says.

She plans to hire students to help create 3D models. “We’ll likely start off with the process of building sketches, just to kind of plan out what we want to make and make sure that the look and feel match the historical accuracy,” Contour says.

With the seed grant, the team will create a five-minute demonstration game that will be used in conjunction with a bigger grant proposal to garner enough funds for a full game, which will take around three to four years to develop.

While the prototype design is underway, Catterall is thinking about how to communicate a history of something that is invisible to the local population. Turning the project into a mobile game will be a way to share information with Syrians as well as UT students.

“I hope it provokes a lot of curiosity about the past and helps people understand their place better and ensures that these portions of history in Syria aren’t lost,” Catterall says.

That history has effects on Texans today as well, Mulder says.

“History is a living thing. It’s not a dry, dusty history book. It’s actually shaping who we are,” Mulder says. “Texas has the fifth-largest Muslim population in the United States, and Muslims have been in the United States from the very founding. They’re part of the story of our country too, so for all of us to understand that this history has shaped who we are, that it’s shaping the present, is what I hope is something to take away from a game like this.”