Founded in 1941, The University of Texas at Austin Marine Science Institute in Port Aransas is the oldest marine research facility on the Texas coast. The institute is dedicated to education, public outreach and research, all with the goal of advancing the understanding of marine ecosystems.

“There’s some amazing, groundbreaking research being done here in Port Aransas,” says Leigh Walsh, broodstock manager and research associate at the Fisheries and Mariculture Laboratory.

Walsh spawns southern flounder and red drum as broodstock manager. She uses the same practices that were pioneered at UTMSI by the founding director of the fisheries services laboratory, Connie Arnold, the first researcher to spawn red drum and southern flounder in captivity.

Walsh has worked at UTMSI for five years, following time at The University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston conducting biomedical research and studying cephalopods. She says she has always loved the water and been fascinated by the ocean.

“Just being on the water every day where I work here on campus — I mean, there are dolphins right on the bulkheads swimming every day,” Walsh says. “It’s just a really cool environment. It’s very beautiful.”

Walsh and her team hold broodstock fish in large recirculating seawater systems, simulating their natural environment’s lighting and temperature to trick them into spawning and providing high-quality eggs and larvae to researchers and graduate students.

“It’s kind of comical because the students are like, ‘We really need eggs,’ and then one day I’m like, ‘OK, we have eggs!’ and they’re like, ‘Oh, I can’t use them today,’” Walsh says. “Playing with Mother Nature is a little tricky sometimes.”

Walsh’s favorite species is southern flounder, which do not spawn readily in captivity, so she uses a process called strip spawning. She gradually adjusts light and temperature in the tanks throughout the year, and once the tanks are in winter conditions, Walsh injects the fish with a hormone to ripen the reproductive system. She then anesthetizes the fish to put them to sleep and squeezes the female flounder’s eggs and the male flounder’s sperm into a beaker.

“It’s amazing to watch because you can see the fertilization happen immediately,” Walsh says. “The eggs will go from sinking to floating, and the floating eggs are the fertilized eggs. They take a couple days to develop an embryo, and then they hatch out.”

Marine biology — people talk about it, but it’s not all Shamu and SeaWorld.

Walsh’s lab works closely with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department on a variety of projects, including a stock enhancement program to bolster southern flounder populations, which have significantly declined due to overfishing and climate change.

“Marine biology — people talk about it, but it’s not all Shamu and SeaWorld,” Walsh says. “There’s just so many cool parts about the ocean that haven’t been discovered or we’re just learning about. It’s pretty exciting to work here and be a part of that.”

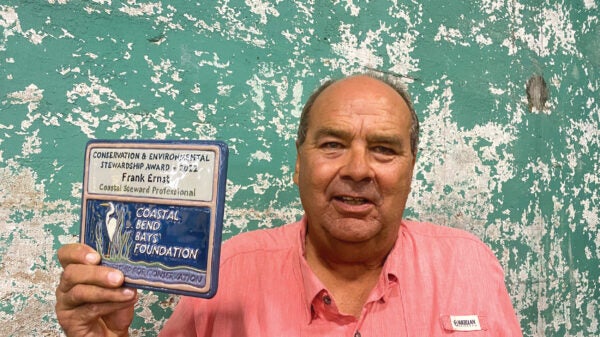

Frank Ernst, boat captain and dive safety officer, didn’t have any experience with the science side of marine life before working at UTMSI, but he says he’s picked up a bit over the years. Ernst maintains the facility’s boats and takes students and researchers out on the water.

“One day it might be mud grabs, the next day it might be pulling a shrub net, or next time it might be getting in the water and cleaning tubes,” Ernst says of the types of sampling and testing done by researchers. “The rest of the time, the dive part is not so elaborate. It’s more making sure everybody’s got their paperwork in before they could do a dive.”

Ernst says he was always on boats starting from the age of 3, when his parents would put a ski belt on him and go out on their boat.

“I started at a marina at age 12, and we lived on the water, so I took my boat to the marina back and forth and just never left the business,” he says.

Ernst originally went into marine repair, but he had a captain’s license and did charter work on the weekends. He preferred running the boats over repairing them, which eventually led him to take the job at UTMSI. Twenty-two years later, he’s still here.

“The students are so rewarding. … They’re really into it, so that’s the cool part,” Ernst says. “They love it, so you get into it with them because they’re just really into the science.”

Every boat trip presents different challenges, with Ernst working to ensure that students and researchers are able to get what they need.

“We’ve got weather, and they’re trying to get mud (samples) and (sometimes) it’s just too rough, so we try to think of different techniques because the boat’s up and down,” Ernst says. “Or maybe it’s the area and that mud’s not right so it won’t hold in the core. So you’ve got to think of a way to bring it up faster so they get their sample. It’s different every time.”

Shayna Whitaker, part-time veterinarian at the Amos Rehabilitation Keep, is also used to every day looking different. All kinds of marine wildlife come through the ARK — she’s rehabilitated sea turtles, raptors, shore birds and once even an alligator.

“He was about 6 feet long, and learning how to do that was a whole different experience,” Whitaker says. “An alligator on the beach who was just completely dehydrated and not feeling good, and we were able to get him good to go and got released.”

Over 1,200 animals came through the ARK’s door last year, and about half were sea turtles. Some get stuck in the jetty, some get hooked or entangled in something, and others end up sick and washed up on the beach.

Whitaker has always had a passion for sea turtles, first working with them with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Mexico and then as a veterinarian in Costa Rica. When her family moved to Texas, she started volunteering at the ARK, shadowing the volunteer vet until she was hired part time.

“They’re so unique, and they’re very stoic. One thing that I’ve learned as a vet, which is super surprising, is they can come back from almost anything,” Whitaker says. “(Some of the turtles) have come in so debilitated that a mammal would never be able to live through (it), and they can. It takes months and months, but they’re resilient.”

Whitaker has worked at the ARK for four years, and since the day she arrived, she’s heard talk about getting a new rescue center built for the facility, replacing a building that was demolished after Hurricane Harvey. In September, the building finally opened, complete with nearly every diagnostic tool imaginable — a digital X-ray, ultrasound machine, endoscope and lasers.

“It is completely amazing. I’m sitting in my surgery suite right now, which is beyond awesome,” Whitaker says. “It’s going to make such a difference for all the care that we can do.”

With the new center, Whitaker and her team will be able to do far more sea turtle surgeries and take in many more birds for rehabilitation, leading to more of what she says is the most rewarding part of the job: releasing the animals back into the wild.

“We’ve had turtles that come in with half of their shell off and their lung exposed, and it takes six months for that to grow back,” Whitaker says. “Or maybe an owl that’s come in that we’ve had to pin a wing, and then we get to actually see it fly away. It’s amazing to get to do that. Especially with the turtles being endangered, we hope we’re really making a difference.”