There never were good old days where adults felt 100% confident talking to teenagers.

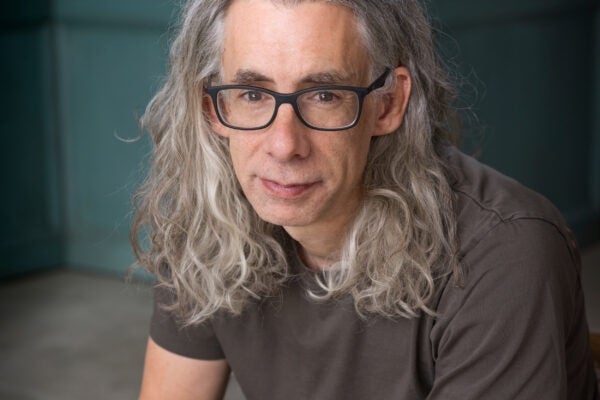

As a kid, David Yeager never really enjoyed school. “I just had this feeling teachers didn’t like me. I felt like I was too energetic and asked a million questions,” he says. “It is kind of weird that I never left school because I didn’t particularly like school very much.”

Years later, Yeager’s life remains deeply entwined with education. The Raymond Dickson Centennial Professor of Psychology has spent more than 13 years with The University of Texas at Austin, co-founding the Texas Behavioral Science and Policy Institute and creating the Fellowship Using the Science of Engagement, known as FUSE — a program for math teachers to learn motivational teaching techniques.

Yeager began a new adventure in 2024 with the publication of his first book “10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People.” In it, he connects psychological research with stories of influential mentors to illuminate how older generations can meaningfully engage with adolescents.

Before entering the world of psychology, the Houston native, motivated by a love of community service, became a middle school English teacher and basketball coach in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

“I was really embedded in the community,” Yeager says. “I doubled down on inspiring (students) and getting to know their families. I went to a million quinceañeras, confirmations, baile folklórico and all that kind of stuff.”

Yeager eventually traded teaching for educational research, hoping to find concrete ways to improve motivation in students. “10 to 25” is the culmination of his scientific work, which he says he delayed sharing for over 10 years.

“The only thing I really care about is doing science, so writing a book feels like a distraction,” Yeager says. “When people first started contacting me almost 10 years ago … I basically said no because I was like, ‘I have a lot of real research to do before I’m going to write a popular version of this stuff.’”

After years of pressure from his agents, Yeager says two things compelled him to finally write the book. First, he saw authorship as the chance to develop new ideas he hadn’t yet explored in his research — which led to his discovery of the mentor mindset framework, one of the primary concepts in “10 to 25.” Second, he was tired of giving keynote presentations without being able to share a tangible extension of his research.

“I was giving talks all over, and people wanted me to leave something behind after my talk for them to interact with,” Yeager says. “All I could tell them was to buy other people’s books, but I didn’t really like other people’s books, so it was better to have it be exactly what I think rather than what someone else thinks.”

In “10 to 25,” Yeager debunks neurobiological incompetence, which he calls the antagonist of the book. It’s the idea that young people’s brains are inherently underdeveloped and lacking in rationality. He says this ill-advised belief has led to decades of failed approaches to youth outreach, frequently ignoring the autonomy of young people.

“We come up with stuff like D.A.R.E. or ‘Just Say No’ or ‘Think. Don’t smoke’ or any other anti-bullying program that’s super lame and doesn’t work,” Yeager says. “Because of this incompetence model, we take ineffective approaches to changing adolescents.”

Yeager offers his mentor mindset as a productive alternative. It challenges mentors to value young people as independent thinkers rather than treat them as problems to be controlled. By centering young people’s desire for status and respect, adults are able to directly communicate constructive criticism while maintaining high standards.

The mentor mindset combats one of society’s oldest (and most misguided) assumptions about young people: They present a threat to traditional ways of life.

The illusion of moral decline is a psychological phenomenon in which older age groups continuously perceive younger generations as worse off morally. Coined by a pair of Harvard researchers, the pattern can lead to oversimplified conclusions that blame young people and societal advances for imperiling the social fabric.

“When you think the reason for moral decline is very recent, then the most logical way to solve the problem is to roll back the clock,” Yeager says. “You end up with adults who are very reactionary and turn conservative in the sense of not liking whatever culture and trends have happened in the last few years.”

However, as Yeager notes, the problem is that there are no perfect times to roll back the clock to. “There never were good old days where adults felt 100% confident talking to teenagers.”

Yeager says the impulse to oversimplify young people’s mindsets and motivations can shape how educators and mentors offer opportunities. Yeager argues that there are two pitfalls to avoid: “enforcers,” who maintain arbitrarily high standards for the sake of exclusivity, and “protectors,” who lower standards in the name of inclusion.

The debate over balancing meritocracy with equity doesn’t need to exist, he says, and the most effective strategy, termed inclusive excellence, proves that the two can coincide.

“There’s a tension seemingly between inclusion and excellence, so the key idea behind that term is to say that you can do both,” Yeager says. “You shouldn’t give ammunition to people who say that inclusion comes at the cost of lower standards, and at the same time, we should challenge the idea that excessively high standards are unbiased because they’re not.”

Yeager hopes readers’ main takeaway from “10 to 25” is the potential to grow, whether it’s in the lab, a college classroom or at home with family.

“You can kind of screw it up once, and then go have a conversation with a young person and say: ‘Look, I didn’t handle this right. I still need you to do what you’re supposed to do, but I should have been more curious about what was going on with you,’” Yeager says.

“You’re not stuck in one mindset or another. You can change, and you can get a do-over.”