The sun was just beginning to set over Waller Creek on a warm February day. Dozens of onlookers stood quietly atop the bridges over the reflective, unmoving water.

Rosemary Candelario, a self-described scholar artist and an associate professor at The University of Texas at Austin’s College of Fine Arts, glided smoothly across the water’s mirrored surface in an ornate wooden boat. A local musician named Sarah Ruth stood on the edge of the creek playing a waterphone — an instrument made of a resonant steel bowl filled with water and surrounded by bronze rods — as a gentle breeze guided its haunting ringing through the air.

Candelario’s performance, titled “aqueous,” utilizes the Japanese dance form butoh to bring attention to the ecology and cultural significance of Waller Creek. It was one of the first offerings of the 2025 Texas Science Festival, a two-week-long celebration of Austin’s scientific community organized by the College of Natural Sciences.

The festival began virtually in Spring 2021 and has rapidly expanded since, offering a wide range of programming — demonstrations, performances, panels and night-out activities — in collaboration with scientific organizations and communities across campus and throughout the state.

New in 2025 was the category “art-science intersection,” which housed Candelario’s “aqueous” performance, which was also hosted by Planet Texas 2050. In an interview, Candelario reflected on the power of dance as an artistic medium to communicate scientific messages.

“Science is great at facts and numbers and all the quantitative stuff, but really art can take us into experience and different ways of knowing that’s harder for science,” she says. “Working together, we can do different things, you know? We can tackle large problems together.”

Candelario explains that, unlike modern dance styles, butoh doesn’t rely on a set vocabulary of movements. As a performer, that physical freedom allows her to confront Waller Creek’s unpleasant truths. The water has a history of pollution, and colorful bits of trash poke out of the dirt along the sides of the creek.

“I tried to really embody that tension in my body and in the struggle of the piece,” Candelario says. “In an urban creek, it’s not just beautiful nature. … We put bad things in there, and it makes us think of the complicated ways that water is in our life.”

While “aqueous” challenged the audience to slow down and reflect on water’s existential purpose, other events provided dynamic conversations about ongoing conflicts within the scientific world.

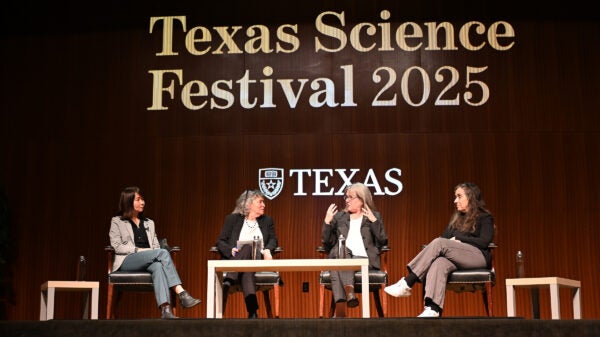

“Shattering Barriers With a Laser Focus” offered visitors a chance to hear from three pioneering women in physics — Nobel laureate Donna Strickland, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Director Kimberly Budil and UT’s own Quantum Institute Co-Director Elaine Li.

The decorated physicists sat onstage in the Lady Bird Johnson Auditorium and answered questions about trust in science, attacks on research and the intricacies of chirped pulse laser amplification.

A recurring theme in the festival’s programming was how can scientists better communicate with the public and make science more accessible.

When asked about the loss of trust in expertise, Strickland, a Canadian physicist, said that the COVID-19 pandemic was akin to a live science experiment playing out in front of people’s eyes. Scientists understood that mistakes had to be made to learn more about the virus; however, the general public was frustrated by continuously changing quarantine protocols.

“The part of the public who doesn’t understand how science works says: ‘These guys don’t even know what they’re doing. Why are we listening to them?’” Strickland added. “They would rather listen and take science advice from somebody with no science training.”

One of the festival’s lead organizers, Heather Leigh, says a goal of the event is to create an avenue for the public to interact directly with scientists and see what research is ongoing in their communities.

“You could see lives being impacted by science in such a beautiful way, and I think there were lots of little moments like that throughout the festival,” Leigh says.

Leigh is the assistant director for community engagement at the College of Natural Sciences and works closely with Director of Communications Christine Sinatra to organize the festival. When asked about working with other colleges at the university, Sinatra says it is easy for people in different fields of research to feel isolated from one another.

“I think at this particular university, we do so much in our own silos that we forget how much happens just right over there,” Sinatra says. “If we can remind our community that the university is a resource for ideas and excitement, … we can be this space for reminding people about what the university has to offer.”

One of Leigh’s favorite events, “Memory Matters,” fused music and study to showcase research done by the labs within the Department of Neuroscience.

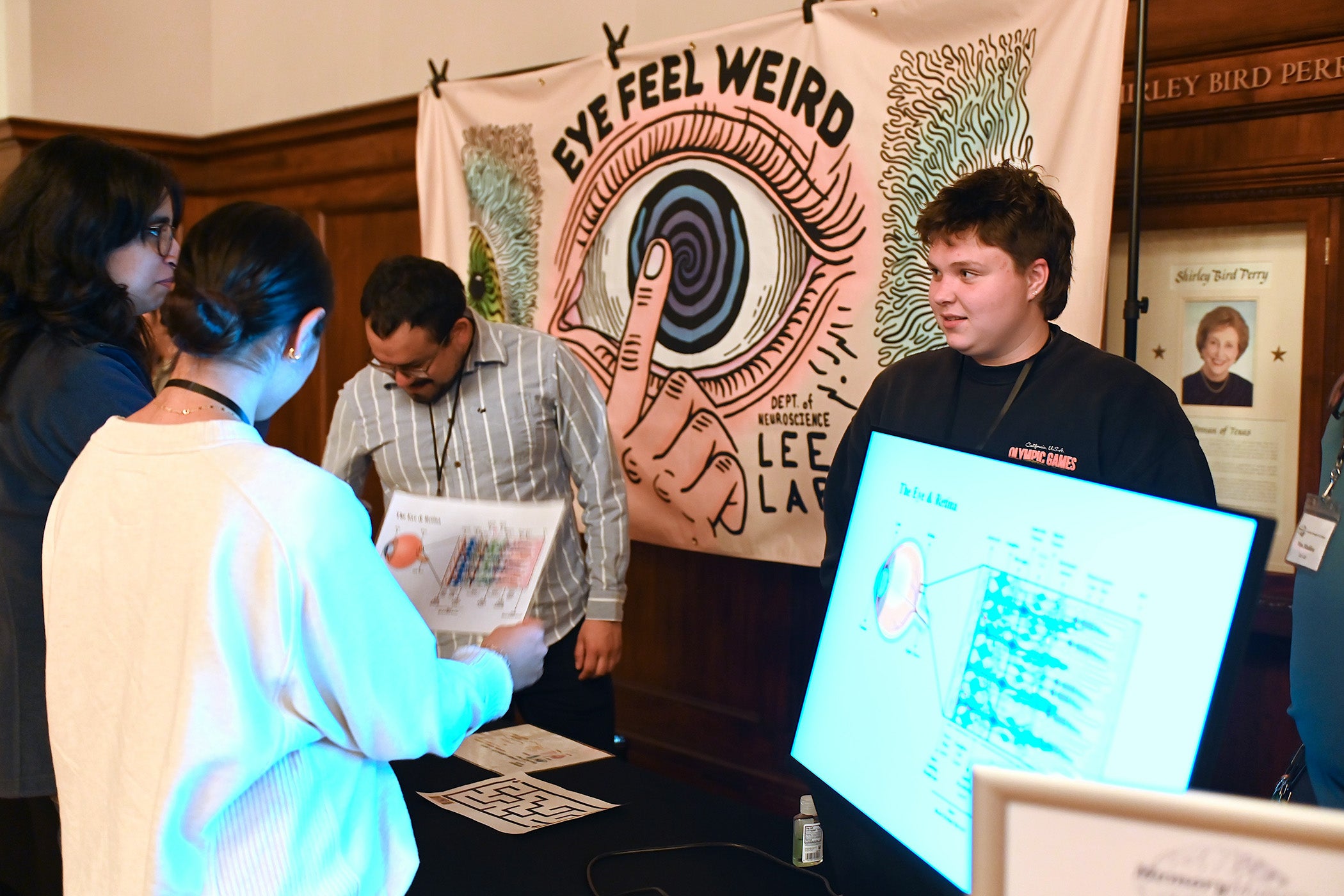

On the day of the exhibition, attendees circled the outer edge of the Texas Union’s Shirley Bird Perry Ballroom. Researchers and nonprofits hosted quirky demonstration tables that lined the walls.

In one corner, participants donned distorted glasses that made playing catch the ultimate challenge, resulting in the inevitable pelting of the graduate student assistants. On the other end of the room, professor Laura Colgin encouraged onlookers to step together in rhythmic unison while explaining how dancing can improve memory and build resilience to degenerative diseases such as dementia.

After an interactive hour of learning, a quintet of musicians prepared to play at the front of the ballroom as part of the College of Natural Sciences’ Musical Memories concert series, which emphasizes the healing power of music. The group’s tender yet energetic performance of Franz Schubert’s “Trout Quintet” evoked Candelario’s belief in art’s power to share scientific knowledge through unconventional means.

“I’m really excited about how we can look at it through a creative lens — offer more programming that’s perhaps a lecture or a talk, but paired with something else that brings the science to life,” Leigh says.

The panel for “Memory Matters” featured a group of neuroscience experts from UT’s Center for Learning and Memory, who dived into scientific rabbit holes, fielding questions about social media, children’s recollection abilities and the impacts of chronic stress on the brain.

However, scientific exploration at the festival was not confined to the Forty Acres. One of the week’s final events would step away to rolling grass and open skies in the southwest corner of Austin.

Sunlight poured through the Great Hall’s floor-to-ceiling windows at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. “Learning, Sharing, Adapting With Plants” invited guests to explore science through historic practices led by local Indigenous townships and environmental nonprofits.

Visitors sampled cedar tea, examined native corn species and handmade instruments in the Central Texas Cherokee Township display, and tested their seed identification skills with Urban Roots, an Austin nonprofit that runs community farms throughout the city.

After the fair, attendees funneled into the Wildflower Center’s sloped auditorium for a keynote presentation from award-winning ethnobiologist Nancy Turner. Turner used her expertise to guide the room through centuries of native migration patterns, language shifts and traditional cooking methods. As she shifted to the Q&A portion of her talk, questions popped up from young children, curious students and experienced researchers alike.

Throughout the festival, an unmistakable motif surfaced: Scientific exploration cannot function in isolation.

Both Sinatra and Leigh say the science festival relies on the year-round communal effort from campus staff and faculty. “There would not be a festival without all the various organizations, units and departments that we are working with,” Leigh says. “It is truly a cross-campus collaborative effort. … It’s our partners who are making most of it happen.”

Sinatra went on to say that in a world where research and education are becoming hotly debated political topics, bringing together people across campus was a much-needed chance to celebrate the accomplishments of UT’s scientific community.

“Bringing people together all in the name of science, that’s really a wonderful thing,” Sinatra says. “I think there were a lot of feel-good moments, and we all need feel-good moments right now.”