The goal of the Tower restoration now underway is to return the University’s emblematic landmark not to what it was before the rust set in but to its original 1937 state. Knowing exactly what it looked like then, however, is trickier than you might think.

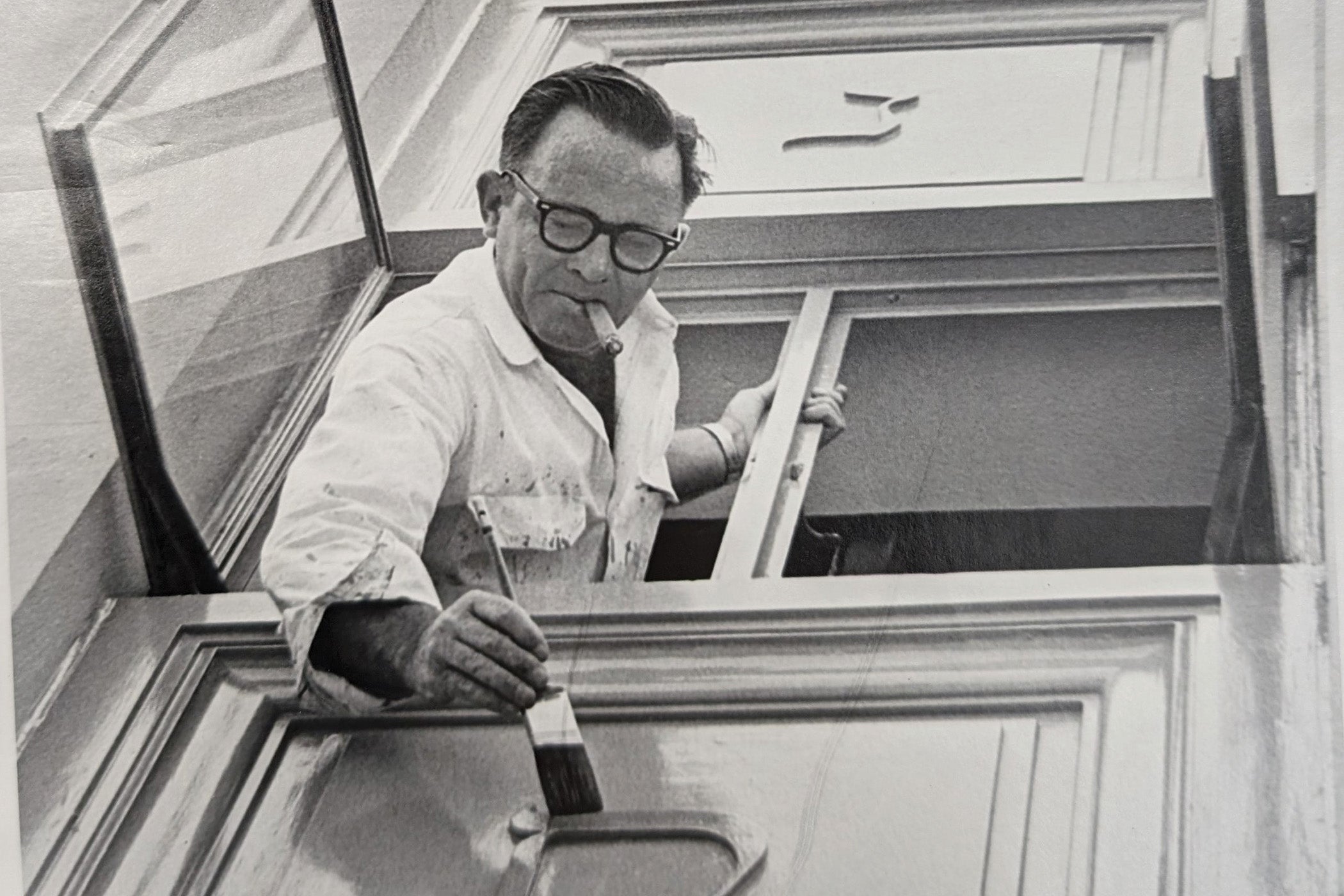

Sure, we have beautiful, detailed color drawings, but sometimes those plans weren’t followed. We also have lots of photographs, but, of course, those are black and white. Sussing out just what was what requires a detective with highly specialized skills, and UT has just such an expert in Kim Barker.

Barker, UT’s first historic preservation planner, came to the University two years ago, having spent a number of years with the Texas Historical Commission. (Texas bona fides don’t get any stronger than working for three years on the Alamo.)

What arguably will affect the look of the Tower most is the restoration of the spandrels, those rusty metal panels that separate each window from those above and below it. But what color were they originally? After some sleuthing, Barker was surprised to learn from 1937 black-and-white photos that each spandrel was painted in two different shades. To find out what those colors were, conservators had to go through numerous layers of paint to reach and then analyze them.

What they found was that each spandrel on the lower, first phase of Main, finished in 1933, had a dark gray center surrounded by a thick border of medium gray. On the Tower itself, the scheme was reversed so that the flat areas of those spandrels (which are double panels) were medium gray, and the recessed borders were dark gray. And the two-tone scheme went all the way up. “It was the original construction, and then it never happened again. We just went simple! We went to one color,” Barker says, mainly whites and creams.

But spandrels are not all that morphed over the decades. “The original drawings showed gilding on the stonework, and the early photos showed gilding on the stonework, but not the same gilding,” Barker says.

The alphabet letters on Main’s north side were gilded, then painted over. There also was gilding on parts of stonework near the clocks, which disappeared over time. Conversely, the clocks’ hands and numbers were originally black but were gilded later. All of that will return to its 1937 state.

When preservationists reached the 10th floor, just before the Tower protrudes up out the building’s north side, they were surprised to discover that a balustrade along a rarely accessed balcony had been encased. Inside that stone casing, many of the balusters were crumbling, so this covering must have been deemed the cheapest fix for the eyesore, even though it departed from the design and original construction.

When the restoration is complete, observant visitors will notice much more color than they remember, especially on the soffits, the undersides of the eaves of Main, which have faded over the years. Barker hit the jackpot when conservators discovered a part of the original soffit that had been encased after just three years, when what is now the President’s patio was constructed, creating a weather-protected time capsule that preserved the vibrant colors.

Sometimes, though, the 1937 reality is simply not practical. Take the canvas awnings Main originally sported along its ground-floor windows. Recreating and installing those would require frequent cleaning in perpetuity. Still, she thought long and hard: “We looked at whether they could be made retractable, but that would require running power to them, which would then modify the building in other ways.” Moreover, the awnings were used to shade the windows because the Main Building was not air-conditioned. So, re-creating them would be going to great expense to address a need of yesteryear that, thankfully, no longer exists.

Barker grew up outside Chicago and earned her bachelor’s in interior design at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. There, she took a number of classes related to historical architecture but did not know that the field of historic preservation even existed. She moved to Austin the first time in 2000. (She muses about finding someone on the early internet who would rent her a room for 30 days and pick her up at the airport.) Three years later, Barker began a master’s at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. After graduating and bouncing around for a few more years, she remembered Austin fondly and, embracing the sun and warm weather as many Midwesterners do, returned to the capital city in 2008 and has been working here in preservation ever since.

Other current projects of hers include the interior of Battle Hall, the ground floor of which originally had a vaulted ceiling. When air conditioning came in, the ceiling was dropped to accommodate the machinery. This was done in numerous buildings across campus, she says. “This is the first building where we’re restoring that ceiling. Now, AC can be small enough to squish it up there and restore the vault below the AC.”

She also is working on projects at Littlefield Home and Carriage House and Little Campus, and she is working to resurrect the oldest structure on campus, the Watson House. UT acquired this 1853 home on Waller Creek just south of MLK Jr. Blvd. in 1973.

Barker is building a website that will chronicle campus development and document our most historic buildings. When it comes to history, a detective’s work is never done.